Organ voluntary: transplant girl back as medic in hospital that saved her life

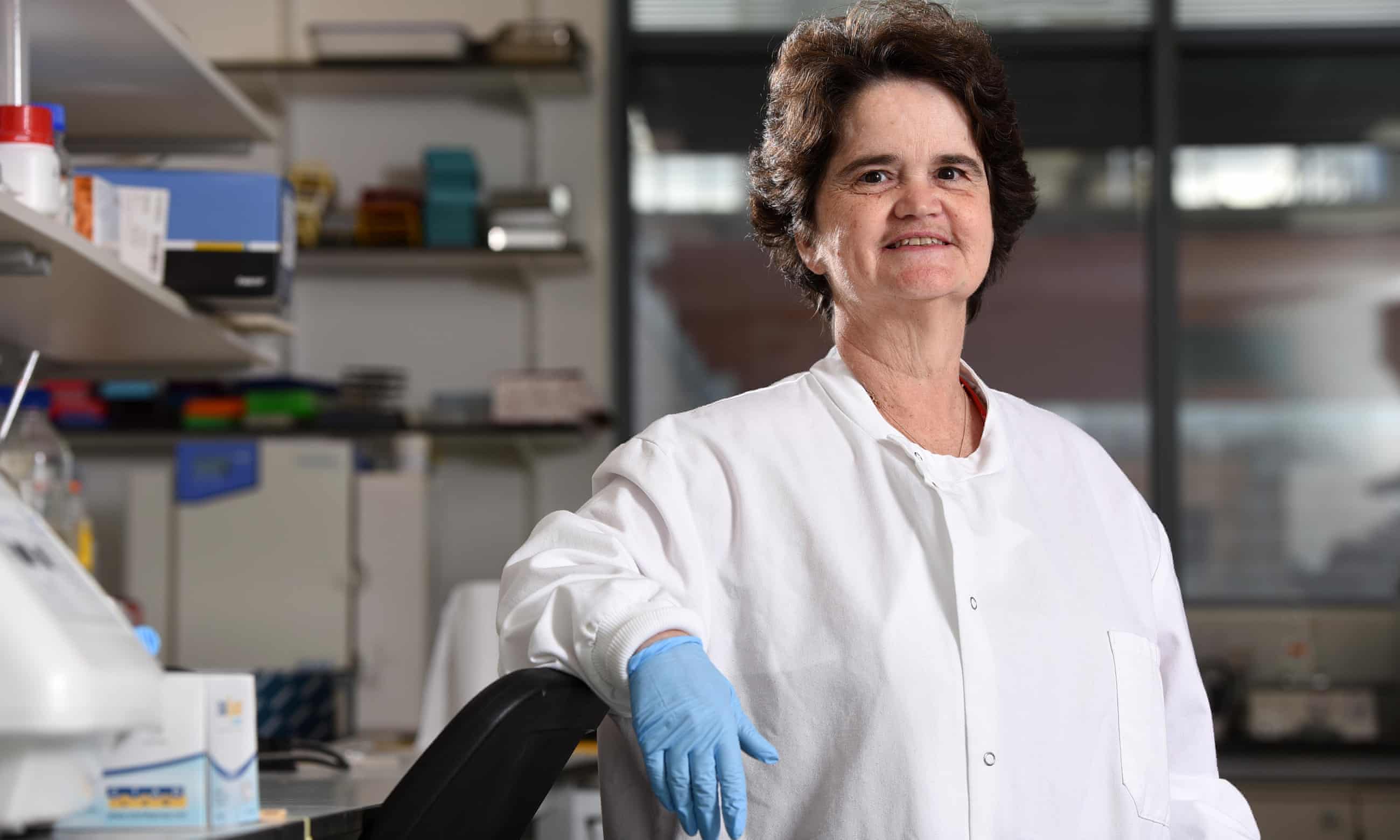

Claire Corps had a kidney replaced at the age of 11. Now she is a transplant expert - at the Leeds hospital that operated on her

Almost 40 years ago, I interviewed a charming 11-year-old girl who was on dialysis – or a kidney machine, as it was quaintly called then. My newspaper was backing a campaign to increase the then paltry number of people carrying donor cards.

Claire Corps’s family in Ripon, North Yorkshire, had built a garage extension to house the machine and were anxiously awaiting a transplant. So articulate and smart was Claire that she later became something of a poster girl for kidney transplants and appeared on both Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour and Blue Peter.

Her operation came in 1980, thanks to a kidney from a 29-year-old man who had died in Leeds of a head injury. I visited her post-op at St James’s hospital in Leeds, with a teddy bear and a Mike Harding book to hand. We later lost touch.

But recently I thought I would try to find out how long Claire, with her eminently Google-able name, had survived after the transplant. The answer was uplifting. Not only was she very much alive 38 years on, but she is now Dr Claire Corps, a senior researcher in transplant medicine, and a key member of staff at the hospital that saved her life.

Corps has several academic papers to her name and lectures around the world. She sits on five official medical committees at national level – and is helping develop a new way of preserving donor organs pre-transplant for much longer than is currently possible.

It was obvious when she was 11 that Corps was smart, but taking into account the amount of school she was missing because of her health, her scientific career has been nothing short of remarkable, even if her health has not always been perfect.

I shouldn’t really be here. I’ve had three potentially fatal illnesses: renal failure when I was eight, two brain haemorrhages when I was 16 and neurosurgery, then liver failure in my 20s. My kidney transplant was the first success they’d had at St James’s with such a tiny child. Then I needed a liver transplant – the first time they had ever done a liver transplant in a kidney transplant patient. When I made it to 50 years old, Professor Peter Lodge, who did the liver op and is now my boss here, said I shouldn’t have made it out of childhood.

When we met, she was also awaiting brain surgery on two aneurysms, which, as she said, were ‘waiting to blow, like pipes about to burst’. A calm thoughtful woman, supported by a strong Catholic faith, she admitted nonetheless to being distinctly edgy about the procedure. In the event it worked out fine, and she is preparing to return to the laboratory and continue her work.

“My doctors do say, a little grimly, that I’m unusually complicated,” she said. Before our meeting, she had emailed a list of 10 highly technical questions to the team at the neighbouring Leeds general infirmary who were about to work on her aneurysms.

“They probably won’t welcome such an interrogation, but since I was a child, I have always insisted on knowing the full story. My patient head and my science head do sometimes clash. When I was 16, I was hospitalised in Plymouth with the first of two brain haemorrhages I had swimming in Cornwall and the doctors told me my notes said, ‘Must be told everything.’ It was true; I’d always said the only way I can fight this is if you tell me exactly what’s going on.”

I had imagined 38 years must be something of a record for a kidney transplant, but Corps was anxious to explain that 40- and 50-year survival times for kidney transplants are not unknown today.

Health concerns did block her plan to study medicine after her time at Ripon Grammar, however. “The brain haemorrhages left me paralysed down one side and I had to teach myself to write again and miss a year of school. But I did it. You’re not supposed to be able to have two brain haemorrhages and then get into Mensa. “But I wouldn't have been tough enough for medicine. Going into liver failure as a junior doctor wouldn’t have made me very useful. So the work I do, partly in the lab, partly on screen, suits me perfectly.” Her PhD, which she gained in 2007, is in organ preservation for transplantation.

Corps also finds time to look after her elderly father, take part in the annual Transplant Games (swimming, walking and cricket-ball throwing), and do amateur dramatics. Her partner is a fellow kidney transplant recipient who works for the NHS in Edinburgh. “So as you can see,” Corps said as I was leaving, “life has had its ups and downs. But surprisingly I am still here and trying to put back some of which I have taken out.”

Lodge, her boss, said: “She’s a remarkable woman to have been through all she has and still have the passion to go to work every day and do her charitable stuff. It’s not unknown for people who’ve had transplants to get very interested in helping other people, but Claire has always been extremely bright and that has helped a lot with her science. She’s written a lot of good stuff and we’ve worked together for 25 years on and off.”